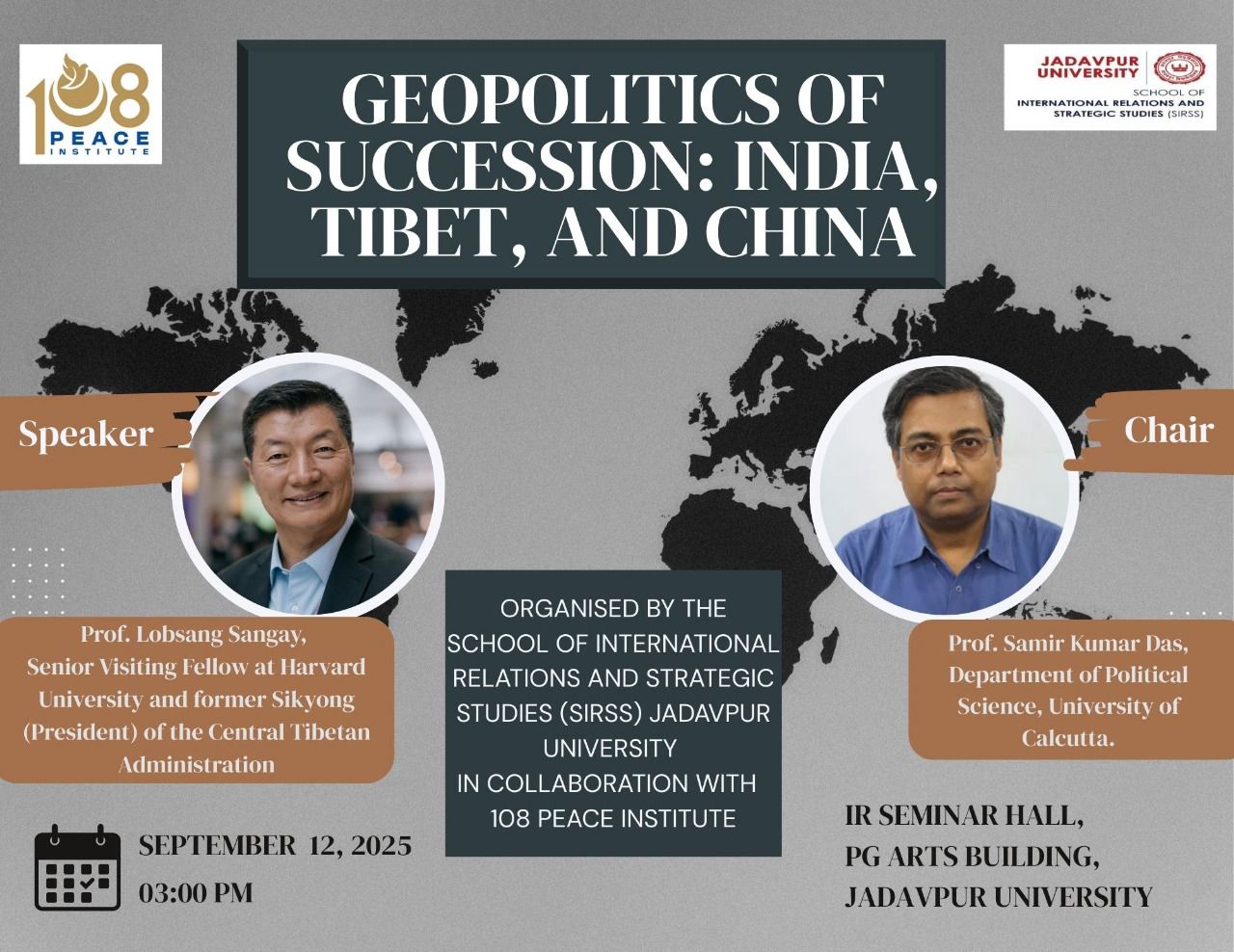

On 12th September 2025, the 108 Peace Institute concluded the final leg of its lecture series in Kolkata, in collaboration with the Department of International Relations at Jadavpur University. Together, they hosted a thought-provoking session on “Geopolitics of Succession: India, Tibet, and China Relations”. The lecture brought together over 70 students and faculty members eager to understand the geopolitical implications of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation for India, Tibet, and China. The session was chaired by Professor Samir Kumar Das of the University of Calcutta and featured Dr. Lobsang Sangay as the keynote speaker.

Dr. Sangay opened the talk by asking the audience to reflect on what the Chinese world order might look like and whether they would prefer a multipolar or bipolar global structure. Drawing comparisons between China and India, he highlighted how in China, senior officials—including foreign ministers and army generals—can disappear without anyone allowed to question their whereabouts, whereas in India, even the temporary absence of a foreign minister would provoke public questioning. He emphasized that in China, questioning the government can result in ordinary citizens—including Han Chinese, not only Tibetans—“disappearing.”

Turning to Tibet, Dr. Sangay noted that it has been under Chinese occupation for more than 60 years. He shed light on the erosion of religious freedom, citing examples such as Muslim children being barred from keeping the name Mohammad, being forbidden to fast during Ramadan, and being forced to eat by Chinese officials. He also drew parallels to Hong Kong, where Beijing had promised 50 years of genuine autonomy under the “one country, two systems” framework, enshrined in China’s constitution. Yet, he said, Hong Kong was denied this autonomy after the British handover to China.

Expanding further, Dr. Sangay explained that China views Taiwan as a “lost brother” to be integrated, despite Taiwan’s resistance. Taiwan enjoys a per capita income of USD 40,000–45,000, while China’s stands at only USD 10,000. Nevertheless, Beijing is preparing its military and missiles to occupy Taiwan, with the declared aim of doing so by 2027. This, he said, is emblematic of China’s expansionist world order. By 2049, China aspires to become the world’s leading power. To achieve this, he argued, Beijing must suppress potential competitors, particularly India, which is positioned as Asia’s potential “number two” in economy, military strength, and demographics.

Dr. Sangay elaborated on China’s strategic approach, describing Tibet as the “palm” and Nepal, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Ladakh, and Bhutan as the “five fingers” it seeks to control. He noted that China has consolidated ties with neighboring countries to encircle India and prevent its rise as a competitor. Citing a New York Times report, he said China has built over 300 villages along and inside the LAC, equipped with concrete roads and helipads, while India still struggles with border infrastructure. China also claims parts of Bhutan as its territory and refers to Arunachal Pradesh as “South Tibet.”

He reminded the audience that historically, today’s China comprises only about 40% of its current territory; the rest was acquired through expansion into Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, and Manchuria. Even today, Han Chinese predominantly live in just 40% of the country. Contrary to Beijing’s narrative of being a peaceful nation, Dr. Sangay stressed that China has always been expansionist. He used the example of the Great Wall of China, originally built to demarcate China from its neighbors—yet now located well within modern China’s borders because the country expanded far beyond the Great Wall.

Dr. Sangay also criticized scholars like Professor Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University, who portray China as a harmonious Confucian society unlikely to invade its neighbors and Taiwan. He countered that “Confucianism is theory, but expansionism is China’s reality.”

On the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, Dr. Sangay underscored its deep geopolitical significance. The Dalai Lama is revered not only by Tibetans but across the Himalayan belt, Mongolia, and even the 3 Buddhist republics of Russia. The Chinese Communist Party—an avowedly atheist regime—seeks to control this spiritual process, not out of religious reverence, but to wield influence over the Buddhist world, said the scholar. He drew parallels to CCP interference in religion, noting that in Xinjiang the party has appointed Imams, and in its secret deal with the Vatican, Beijing effectively nominates bishops, reducing the Vatican’s role to a rubber stamp. He warned that, following this pattern, China could eventually attempt to interfere in India’s religious institutions as well to select the Sankracharyas.

Dr. Sangay delved deeper into how China occupied Tibet, explaining that it was achieved not only through military force but also through “elite cooptation”—the strategy of buying over intellectuals, politicians, journalists, and even ordinary people to secure influence. He emphasized that this practice is not limited to Asia but extends across America, Australia, and Europe.

Sharing personal experiences, he recounted how the foreign minister of Australia once refused to meet him, only for Dr. Sangay to later discover that the same minister was heading the largest think tank in China. Similarly, a former Australian trade minister who signed an agreement handing over a major port to China now sits on the board of a Chinese company, earning nearly 880,000 dollars a year. In Norway, Dr. Sangay was denied a meeting with the foreign minister, who was then affiliated with China’s International Development Committee—today that individual serves as the President of the World Economic Forum. In 2007, the Forum itself welcomed Chinese President Xi Jinping as its chief guest at Davos, rolling out the red carpet and praising China as greater than America.

“This,” Dr. Sangay said, “is the Chinese world order—one in which they buy the elites of the richest countries in the world. If they can do this abroad, we must be even more concerned about West Bengal and India as a whole.”

He pointed out that many in India are eager to do business with China, but questions why Indian actors and actresses, despite their immense wealth, endorse Chinese companies for just a few more dollars. He expressed dismay at seeing Indian cricketers wearing uniforms emblazoned with Chinese brand logos, “as if they were playing for China rather than India.” He asked why Indian companies cannot sponsor the national players instead.

Dr. Sangay warned that Chinese influence has already penetrated Bollywood, cricket, journalism, and even politics. He stressed that what happened in Tibet is now happening in India: “If India wants to truly understand China, it must first understand Tibet. Otherwise, it will never be able to counter China effectively.”

Highlighting Tibet’s significance, Dr. Sangay explained that it historically functioned as a buffer state between India and China, complete with its own currency, judiciary, and independent foreign policy. He referred to the 1914 McMahon Line—signed between British India and Tibet to deter Chinese incursions—and the Panchsheel Agreement of 1954, which ironically paved the way for China’s occupation of Tibet in 1959 and its invasion of India in 1962. He noted a troubling pattern: each time Indian leaders marked “friendship” anniversaries with China, Beijing responded with aggression at the borders—yet India failed to draw the necessary lessons.

In conclusion, Dr. Sangay emphasized that the issue of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation is not merely a Tibetan matter but a pivotal factor in resisting the Chinese world order. He contrasted India’s model of “development with democracy” with China’s “development without democracy,” citing Amartya Sen’s research to illustrate how freedom of speech in India saved millions during famines, while censorship in China led to mass deaths. Recalling His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s declaration that his reincarnation would take place outside China, in a free world, Dr. Sangay urged the Indian government to respect and support this decision. He reiterated that Tibet holds the key to understanding China’s ambitions: “If India wants to understand China, it must first understand Tibet.” An engaging question-and-answer session followed the lecture, with the audience keen to understand Tibet’s issue in the context of the current geopolitical landscape.